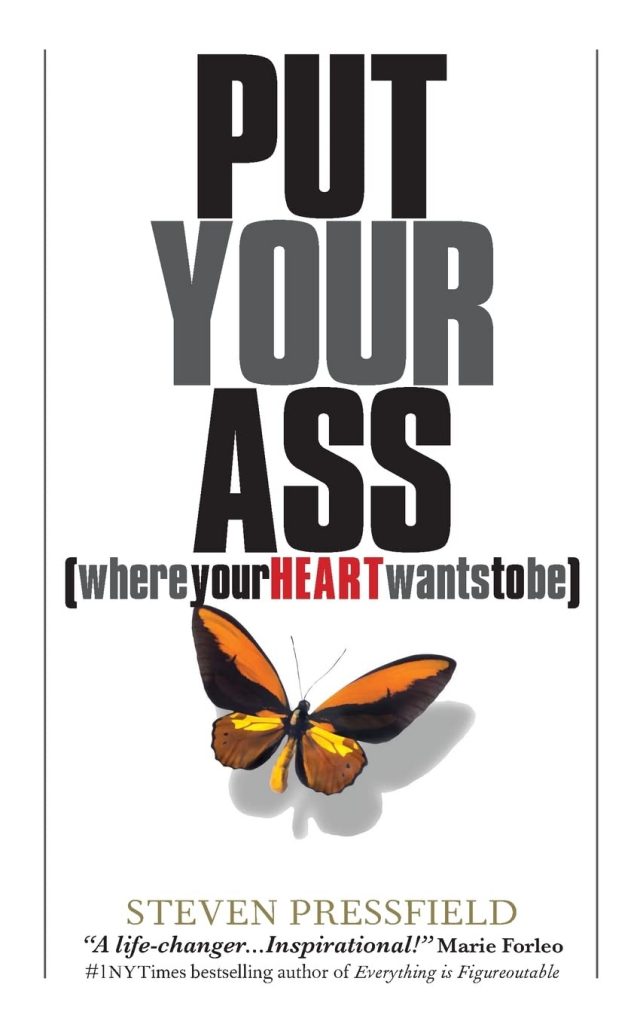

I love Steven Pressfield’s work, and his book The War of Art is on of my all-time favorites which I revisit regularly. So naturally, I was excited when he released a new book. Here’s my summary of Put Your Ass Where Your Heart Wants to Be.

Overall rating: 8/10

In a nutshell review: This is my least favorite of Steven Pressfield‘s books on creative work. Even if you’ve already read The War of Art, I’d probably recommend you re-read it, rather than read Put Your Ass Where Your Heart Wants to Be, because I do believe you get more out of it. At least that’s true for me. I was honestly a bit disappointed by the book, mostly because I had such high expectations I think.

Here are my book highlights:

[…] tremendous power lies in this simple physical action.

This is really one of the core ideas of this book: Simply by doing the physical action of whatever it is you want to do, you're already on your way. Even if you do it poorly, even if you lack talent. By simply doing the physical act, you are so much closer to where you want to be already. (Which doesn't mean that you still don't have a long way to go. But you're much, much closer than you would be not doing the physical act.)

When I sit down to write in the morning, I literally have no expectations for myself or for the day’s work. My only goal is to put in three or four hours with my fingers punching the keys. I don’t judge myself on quality. I don’t hold myself accountable for quantity. The only questions I ask are, Did I show up? Did I try my best?

This to my was so fascinating (and soothing) to read. Just showing up and doing the best you can at that moment is enough. It doesn't matter what the outcome is. It doesn't matter how good it is, or how much output you created. All that matters is that you put in the time, and did the best you could. Not even "the best you could" as in what your theoretical potential is. No, simply: the best you could at that time, being the imperfect and flawed and distracted person you are.

Leave the town or city where you live and move to the hub of the creative or entrepreneurial world where your dreams are most likely to come true.

Pressfield makes a big case for actually physically moving to where the action happens. If you wanna make it in movies, move to Hollywood. If you wanna do a startup, move to San Francisco or Austin. He really drives home that point, saying that yes, you can do so much remotely now via Zoom calls, but by moving there you'll multiply your chances of actually making it manifold.

Glenn Frey was the founding member of the Eagles along with Don Henley. He tells this story (I’m paraphrasing) in the documentary, History of the Eagles. I had moved to LA from Detroit. I was sharing a super-low-rent apartment in Silver Lake with J.D. Souther. We were struggling to establish ourselves as singers and songwriters. The apartment directly below us was Jackson Browne’s. He was as broke and unknown as we were. Frey describes how sound came up through the floor from Jackson Browne’s place to his. All day he could hear Jackson Browne working on songs. Browne would play a song on the piano once, twice, thirty times. He’d stop to make himself a cup of tea (Glenn could hear the whistling teapot), and then he’d go back to the piano and work on the song for another thirty passes, tweaking it and revising it little by little. I realized, This is how you write a song! Not in one crazed pass, not scribbling notes and losing them in your jacket pockets or your glove compartment . . . but sitting down like a pro and working with the material, changing and improving the song over and over, until you had it exactly the way you wanted it.

Books are self-organizing too. So are albums, entrepreneurial ventures, and statues of David. The process unfolds infallibly. Our symphony-in-the-works evolves into four movements, our screenplay orders itself into three acts. If we just keep plugging away at it, the Law of Self-Ordering comes to our aid.

Loved what he wrote here. When he works on a book, eventually a structure comes together, even if at first it seems chaotic and messy and all over the place. Eventually, it finds its shape.

Work—day-in, day-out exertion and concentration—produces progress and order. That’s a law of the universe.

Again this concept of: If you keep putting in the hours, eventually you'll get there, even if it's not a straight line, even if right now it still seems like you're lost at sea.

Can we put our ass where our heart wants to be if we’ve got a family, a job, a mortgage? Yes. The Muse does not count hours. She counts commitment. It is possible to be one hundred percent committed ten percent of the time. The goddess understands.

[…]

James Patterson was creative director of J. Walter Thompson, the mega-ad agency of the fifties and sixties. His dream was to be a writer of fiction. He would come into the office every morning at six. He’d close his door and lock it. For two hours, he wrote fiction. When the advertising day started, he opened his door and became a regulation Mad Man. As of 2022, James Patterson’s books have sold three hundred million copies.

[…]

One hour a day is seven hours a week, thirty hours a month, 365 hours a year. Three hundred and sixty hours is nine forty-hour weeks. Nine forty-hour weeks is a novel. It’s two screenplays, maybe three. In ten years, that’s ten novels or twenty movie scripts. You can be a full-time writer, one hour a day.

I love that whole idea. It's so true—I always feel like I don't have enough time, because I have too many other responsibilities and commitments: my daughter, work, family, friends, fitness... "If only I'd have more time..." But quite frankly: I do think that I have more time than the creative director of a major ad agency. And yeah, it would be nice to have more time, but the truth is also: I actually have more available time right now than I dedicate to doing the work that matters. Realistically, I could spend at least five more hours a week on doing this without having to cut out anything meaningful.

I’m sometimes asked, “How did you keep going all those years without any success?” I couldn’t have answered at the time, except to say that I had no choice. Any time I tried to take the intelligent course, i.e., get a real job, I became so depressed I couldn’t stand it.

Wow. I can relate to this. At some point, what calls you becomes so loud and clear that if you refuse to follow that calling, it just makes you more and more miserable. And I guess at some point it'll get so bad that you really don't have a chance of not continuing on the path that's destined for you.

The first thing I do when I enter my office each morning is say a prayer to the Muse. I say it out loud in dead earnest. The prayer I say (this is in The War of Art, page 119) is the invocation of the Muse from Homer’s Odyssey, translation by T.E. Lawrence,

What an interesting ritual. Actually saying a prayer to the muse out loud, in earnest. Quite frankly, I'd feel foolish to do this, but I'm going to do this for a while, albeit with my own prayer.

I stop working when I start making mistakes. Typos and misspellings tell me I’m tired. I have reached the point of diminishing returns. Steinbeck said he always wanted to leave something in the well for tomorrow. Hemingway believed you should stop when you knew what was going to happen next in the story. You and I, as writers and artists, are playing always for tomorrow. Our game is the long game. When you’re tired, stop.

I like this idea. You stop before your tank is empty, rather than working to the point of exhaustion each time. This way, you'll be much more excited and energized to show up at work the next time, because you still got that thing you want to do ahead of you.

THE OFFICE IS CLOSED

When I finish the day’s work, I turn my mind off. The office is closed. The work has been handed off to the Unconscious, to the Muse. I respect her. I give her her time. If I see family or friends, I never talk about what I’m working on. I politely deflect any queries. But beyond not talking with others, I refuse to talk to myself. I don’t obsess. I don’t worry. I don’t second-guess. I let it rest. The office is closed.

Another valuable lesson here. I don't spend 3 or 4 dedicated, really focused hours a day on doing the work. But it's something that's kind of all day in the back of my mind somewhere. I never hit the off-switch. But I'm rarely ever really on either. And it's impossible to create your best work this way. Having a really dedicated off-time where you free your mind of thinking about the work is good practice.

THE GODDESS VISITS AT NIGHT I said the office is closed. That’s not completely accurate. I set my phone or my mini-recorder on my bedside table.

I thought that was interesting too, and it reminded me of something that Stephen King once said: He doesn't take notes, doesn't record his ideas. For him, if he forgets an idea, then obviously the idea wasn't strong enough. The really great ideas stick with him, follow him, pursue him, don't let go of him. That's obviously a very different approach to Pressfield, but the lesson here simply is: find what works for you.

FORTUNE FAVORS THE BOLD

The seminal action of every pitched battle fought by Alexander the Great was his headlong charge, mounted on his great warhorse Bucephalus, into the teeth of the enemy. Alexander wore distinctive armor and a double-plumed helmet so that his rush, at the head of his sixteen-hundred-strong Companion Cavalry, would be missed by no one on the field. Why did Alexander risk his life like this? First and most certainly, to inspire his men. Alexander believed that the sight of their king charging fearlessly at the foe would compel the warriors of his own phalanx and auxiliary cavalry to emulation, that they would follow their champion’s example and attack with equal fire and passion. But Alexander believed something greater. His conviction was that heaven, witnessing his act of valor and fearlessness, would be compelled to act as well. The heart of Zeus (or whatever we might call chance, luck, fortune) could not look on unmoved. The Higher Dimension would intervene, somehow, some way, in Alexander’s favor. Fortune, Alexander believed, favors the bold.

That's another beautiful idea. That courage actually somehow puts the odds in your favor. Courage gets rewarded. There's obviously a limit to this—putting your life on the line the way Alexander the Great did, not so sure about that. There's probably plenty of examples in history where this didn't work out so favorably. That said, for most of us—most definitely for me—being more courageous will lead to good things.

For writers and artists, the ability to self-reinforce is more important than talent. What exactly is reinforcement? It’s when your coach or mentor tugs you aside and tells you how well you are doing, how proud of you they are, and how certain they are that ultimate success will be yours if you just stay who you are and keep doing what you’re doing. That’s reinforcement. Can you tell yourself that? Without a coach? Without a mentor? Can you be your own coach and mentor? That’s self-reinforcement. When we say, “Put your ass where your heart wants to be,” we also mean keep it there. Self-reinforcement keeps us there. It keeps us committed over the long haul.

I guess that's an important skill. I'm definitely overly critical of myself. I'm a pretty hypercritical person anyway, but with no one as much as with myself. Which is a good trait in many ways I think, because it helps keep me sharp. But it needs to be balanced out. I gotta tell myself more often: Yeah, Omwow, you're doing good here. You're on your way. Keep going!

Henry Miller worked as a supervisor for the phone company in Brooklyn. In Tropic of Capricorn, he called it the Cosmodemonic Telegraph Company of North America. Charles Bukowski worked for years for the Post Office. Can you imagine how “reality” was defined for them by their bosses and by the expectations of others? What was reality? It was that these guys were great writers struggling to find their voices and become the gifts-to-the-world they truly were.

If these guys could write at the level they wrote while doing shitty jobs in a phone company or post office, you and I really have no reason to not do at our own respective level what we can do. We might never be in the same league as Miller or Bukowski, but we might just create something of value for a little tribe of people.

Self-reinforcement is a superpower. It may seem silly when it’s enacted in the moment—some crazy waitress/actress talking to herself in her Honda at a stop light. But in fact that young lady has put her ass where her heart wants to be . . . and she has found the self-talk and self-validation to keep it there.

Love that. I used to be so judgmental of people for doing shit like this. Even when I saw a guy talking to himself in the mirror, I thought: Geez, what a loser! I've come a long way since, and I do make an effort to talk to myself in a much more encouraging way and get better at giving myself pep talks, but I want to do this more. Better look ridiculous and silly while pursuing your dream, than look completely reasonable after having thrown in the towel.

What fascinates me about the character of Alexander the Great is that he seemed to see the future with such clarity and such intensity as to make it virtually impossible that it would not come true—and that he would be the one to make it so. That’s you and me at the inception of any creative project. The book/screenplay/nonprofit/start-up already exists in the Other World. Your job and mine is to bring it forth in this one.

What a beautiful way of illustrating this: You want to see whatever you start working on with such a clear intensity that it becomes true to you long before it becomes actually true. Almost as if you manifest it into existence, just in a less woo-woo way.